Metropole Region Amsterdam

WORLWIDE FRONTRUNNER IN CIRCULARITY

The Amsterdam Metropolitan Area, like the rest of the world, faces the challenge of using resources more efficiently. The growth of the world population, the increase of consumption of materials and the rise in the production of waste is leading to growing scarcity of some key resources, more volatile prices and a severe impact on the environment. This problem of resource efficiency will even exacerbate as a result of the staggering increase in urbanisation. In 1950 30 per cent of the world’s population was urban, while in 2014 54 per cent resides in urban areas. By 2050, 66 per cent of the world’s population is projected to be urban.

The Challenge of Making a Transition to a Circular Economy in the Amsterdam Metropolitan Area

The Amsterdam Metropolitan Area has joined forces to move towards a circular economy because of the great opportunities it could offer the region. The region’s ambition for 2025 is to be worldwide frontrunner infinding smart solutionsfor the limited availability of resources through redesign and the closing of energy, water and material loops. Simultaneously, innovation and new business development will be realised in the Amsterdam region.

The Amsterdam Metropolitan Area is a comparatively densely populated region (2.33 million inhabitants) in which large amounts of products and materials circulate, and many innovative and sustainable entrepreneurs are active. The region has an excellent logistic network across all transport modes (including a main harbour, global airport -Schiphol- and prime railways and roads), and a coordinated spatial planning. It composes of a broad spectrum of economic activities and knowledge infrastructure, while societal support is present for circular economy initiatives.

To promote circular economy municipalities take a variety of initiatives at local level such as promoting the separation of waste by consumers and companies, developing advanced platforms to reuse, refurbish and remanufacture products and supporting circular business development together with the Amsterdam Harbour Authority and the Schiphol Area Development Company (http://hollandcircularhotspot.nl/…/amsterdam-edition-of-hch-mag). A good example of a city approach is Circular Amsterdam (journey.circularamsterdam.com/circularamsterdam).

However, some initiatives require coordination at a higher scale, primarily the region. Therefore, The Amsterdam Economic Board has initiated a circular economy programme at regional level in January 2015 in close cooperation with the Regional Board of Local Governments, business, knowledge institutes and citizens. This programme focuses on closing material cycles (high value recycling of resources, reuse of products and circular design of product- and material chains). Besides this programme a separate, joint initiative has started on the energy transition.

The design of the programme

The circular economy programme of the Amsterdam Economic Board consists of four phases:

Phase 1: Drafting the circular economy programme

Phase 2: Building circular initiatives

Phase 3: Scaling up at regional level

Phase 4: Mainstreaming at national level

From 2015 – 2018 the programme focused on phases 1 and 2. In 2019 phase 3 has started for those initiatives that realised new business development. Phase 4 is not yet in sight. Phase 1 – Drafting the circular economy programme – evolved relatively fast due to the comparatively favourable cultural and political climate in the region. This positive climate has not only enabled the emergence of the circular economy programme of the Board, but also triggered other circular initiatives at the local level and within industry. Phase 2 – building circular initiatives – is key in the implementation of the programme and can cover a variety of activities. After four years of implementation the results of the programme were monitored and evaluated. Reflecting upon these results led to the start of a next round of activities in January 2019.

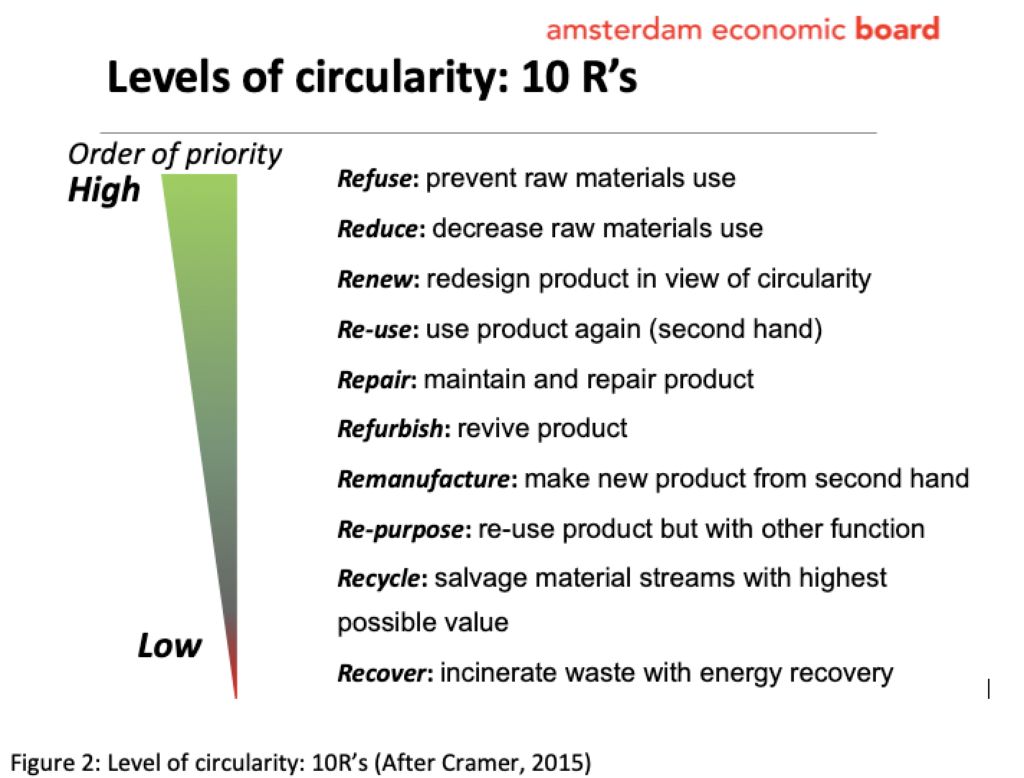

To stretch the circular ambition of the programme, the aim was to set up activities that focus on the highest possible steps on the ladder of circularity (Cramer, 2015).

Two major strategies

Based on the ladder of circularity the strategic choice of the programme in 2015-2018 was to focus on two major strategies:

- Circular procurement.

The aim of this strategy is to stimulate circular products through circular procurement executed by local governments and other contractors (for example businesses and knowledge institutes). Three communities of practice were set up successively, with in total 31 representatives of procurement or sustainability divisions. The goal was to gain knowledge about circular procurement, exchange experiences and explore potential cooperation. Each community of practice consisted of 6 sessions, in which the participants learned from each other and acquired the necessary expertise to implement circular procurement within their own organisation. The participants chose a few procurement trajectories to start with and planned to add more in the coming years. It was left to the participants themselves to decide which trajectories they would select. In order to be as innovative as possible, the participants were encouraged to include start-ups as well as scale-ups. Investments were made particularly in the following five product groups: demolition and construction, office furniture, road signs, catering, and data servers and ICT business equipment.

Key results were: 150 million euros invested in circular procurement. Moreover, 31 municipalities and the two provinces of the region have signed a manifesto, which committed them to realise 10% circular procurement by 2022, 50% in 2025 and 100% as soon as possible.

- Closing the loop of resource streams

The aim of this strategy is to create ecosystems in which resource streams are recycled and if possible reused and redesigned. The following nine main resource streams, consisting of many sub-streams were selected: biomass, construction- and demolition material, electronic and electric products, non-wearable textile, plastics, diapers, mattresses, servers of ICT sector and metals.

These resource streams were chosen because of their high volumes, large environmental footprint and potential for innovative improvement in terms of recycling, product reuse and redesign. Priority was given to household resource streams, because more public data are available about those compared to business resource streams. Some business resource streams were also included because these were prioritised by members of the Amsterdam Economic Board (viz. data servers, demolition and building, metals and the resource stream of the food industry, which is a sub-stream of biomass. The objective was to build consortia of parties that were willing to jointly set up challenging circular initiatives.

The Board designed and adopted a generic approach to generate and select the most promising options for closing the loop of each resource stream. Experiences showed, however, that this generic approach had to be applied flexibly. The overall approach is described in Figure 3.

The approach adopted has often led to innovative steps towards the circular economy. The parties involved strived for ambitious solutions, both for generating new products (flavour additives, phosphate and calcite, insulation material and regenerated clothes, diapers and mattresses) and the reuse of products (building materials and data servers).

New business models were adopted in about 60 per cent of all cases. The most often applied model was the ‘shared costs and benefits model’, in which key actors jointly estimated the overall cost-result ratio in advance and made a calculation that reflected the share of each actor in a well-balanced manner. Such an honest account of the costs and benefits was often needed to build a viable consortium, which was economically attractive for all consortium partners. Other new business models that were applied were: leasing, sharing and the introduction of a cooperative or voluntary producer responsibility scheme.

Results

The key results were high value recycling and product-redesign and reuse of 20 resource streams. Examples are:

High-grade food waste processing

Waste streams from the food industry consist of valuable resources, which can be reused, for example to produce flavouring additives. Plans for a bio-refinery that reclaims nutrients are being developed by a start-up (a spin-off from a flavouring additive manufacturer) in collaboration with the University of Amsterdam’s Green Campus. To obtain sufficient residual food waste streams, cooperation is needed with major food companies in the region. The Board actively supported the making of this consortium. Also read: High-grade food waste processing

Roadside grass as a green raw material

The processing of organic waste from public green space (e.g. grass and clippings) focused on recycling organic waste from public green space to produce energy and resources. The Board helped to form a consortium consisting of a recycler, three public authorities that provide the waste material and a start-up that is able to make insulation material from the reclaimed resources. Also read: Roadside grass as a green raw material

Green Energy Factory

The production of green gas, heat, compost, citrus fuel and water from organic waste has been set up by Meerlanden, one of the main waste incineration facilities in the region. Their so-called Green Energy Factory was built in Rijsenhout, just south of Amsterdam Airport Schiphol, and uses vegetable, fruit and garden waste from nine municipalities and 4,000 companies in the region as input. The Amsterdam Economic Board helped to set these developments in motion by conducting thorough market research and bringing together the parties concerned. Also read: Organic waste: the start of something beautiful

Diapers

The Board called for the reclamation of resources from recycled nappies in order to produce R-plastic, sterilized cellulose and sterilized super absorbing polymers for new applications. Having investigated the most promising options available in the market, the Board approached the waste incineration company in Amsterdam to determine its interest. As nappy recycling was appropriate to the diversification of its portfolio, the company was willing to co-invest in demonstration and commercial scale facilities. The next step was to select the most appropriate candidate, which happened to be a scale-up – a spin-off from a nappy manufacturer. Together with this company, the Board and the waste incineration company built a consortium with a customer and various municipalities to organise the collection of nappies. The initiative could then be launched. Also read:Pilot launched to recycle millions of nappies

Mattresses

The increasing pressure on manufacturers to improve the redesign and recycling of mattresses became an incentive for action. This pressure is primarily caused by the technical problems that waste incineration facilities encounter in storing and processing mattresses. The existing alternative pathway – mattress recycling – is very expensive, which implies that it is barely possible for the two Dutch scale-up mattress recyclers to survive. To solve this stalemate, the Board has initiated a national initiative to set up a voluntary producer responsibility scheme. This includes a small price increase for each mattress sold in order to finance collection and recycling and to promote the redesign of mattresses for reuse and recycling through innovation. Mattress manufacturers are now taking the lead in decision-making on this plan. In anticipation of the introduction of this initiative, an innovative manufacturer has already managed to redesign and sell a ‘circular’ mattress that sets an example to the entire sector.

Data servers

The case of data servers has been initiated by the Board in view of the rapid expansion of the data centre sector in the Amsterdam Metropolitan Region. The Board has approached key actors in the sector to help increase the circularity of data servers. A consortium consisting of a manufacturer, two industry associations and a data centre was formed. The first problem was a lack of knowledge about what happens to data servers once they are discarded. As there is no overarching administrative system, equipment is entirely untraceable, which hampers high value recycling. A Board partner adopting blockchain initiatives helped to address this problem. Knowing what happens to data servers after use also increases the interest in reuse (including the refurbishment of data servers in whole or in part). Consequently, SMEs and niche companies that can provide these services have become more involved. The data servers themselves are produced on the world market, which makes it hard for regional bidders to exert a radical influence on the product design. Also read: Half a million data servers a year discarded in the Netherlands

Jobs of the Future

The circular economy programme of the Amsterdam Economic Board also pays attention to the potential of the transition towards a circular economy for circular jobs.Therefore a ‘Manifesto Circular Education’ has been formulated and signed by 15 frontrunners in education (from primary to scientific education) in the Amsterdam Metropolitan Area. They have committed themselves:

– to incorporate the ideas of the circular economy in the curriculum,

– to promote that the theme becomes central to the relevant programs

– to anchor circular education in the mission and vision of the institution. Also read:

https://www.amsterdameconomicboard.com/en/circulairmanifest

To support the above initiative the consultancy firm Circle Economy and Erasmus University Rotterdam have written the report “Circular jobs and skills in the Amsterdam Metropolitan Area”, the world’s first regional deep-dive to explore the character of jobs and skills in the circular economy. Additionally, it provides practical actions for urban policymakers that to boost the development of a future-proof and circular workforce. The report was produced for the City of Amsterdam and Amsterdam Metropolitan Area. The Board actively supported the development as steering committee member. Also read:

https://www.circle-economy.com/…/Final-Circular-Jobs-and-Skills-in-the-A…

Next steps

In the coming four years (2019-2023) the circular economy programme of the Amsterdam Economic Board will focus on:

- Scaling up the circular initiatives that have proven to be successful on a regional scale

- Enlarging and strengthening the circular procurement community in the region

- Initiating a next round of initiatives to close the loop of resource streams, particularly focussed on industrial resource streams

Drivers of success

The main lesson we have learned is that the success depends on a number of main drivers that are relevant for all initiatives. Firstly, there should be one or a limited number of initiators that act as inspiring ‘transition brokers’. Secondly, cooperation across the product chain (including end-users) is key, including trust and mutual respect. A combined effort on the part of innovative companies and forward-thinking universities, plus a government to stimulate, facilitate and connect them, is crucial, as together they know more, and can achieve more. Thirdly, new financial and organizational arrangements are important to create a convincing business case. Finally, additional tailor-made incentives need to be attuned to the specific product-/waste stream at stake. One of the main incentives is circular procurement.

Further reading

J. Cramer, Moving towards a circular economy in the Netherlands: Challenges and directions, in Proceedings van The HKIE Environmental Division Annual Forum, ‘The Future Directions and Breakthroughs of Hong Kong’s Environmental Industry, Hong Kong, 17 April 2015, pp. 1-9.

J. Cramer, The Raw Materials Transition in the Amsterdam Metropolitan Area: Added Value for the Economy, Well-Being, and the Environment, Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 2017, 59:3, 14-21.

J. Cramer, Key Drivers for High-Grade Recycling under constrained Conditions, Recycling, 3,16, 2018, pp. 1-15.

More information:

Claire Teurlings (c.teurlings@amecboard.com)